Law firms that understand their economics are more likely to capture and maintain an edge in today’s highly competitive legal market. Optimizing their economic model, or tethering it to the market, achieves even greater stability and larger profits for the firm. If you don’t have an operating model and want to develop one or improve your current model, here is how.

Download our eBook "Building a Law Firm Economic Model" which includes a one-page, editable Economic Model Template

Download our eBook "Building a Law Firm Economic Model" which includes a one-page, editable Economic Model Template

What is an economic model for a law firm?

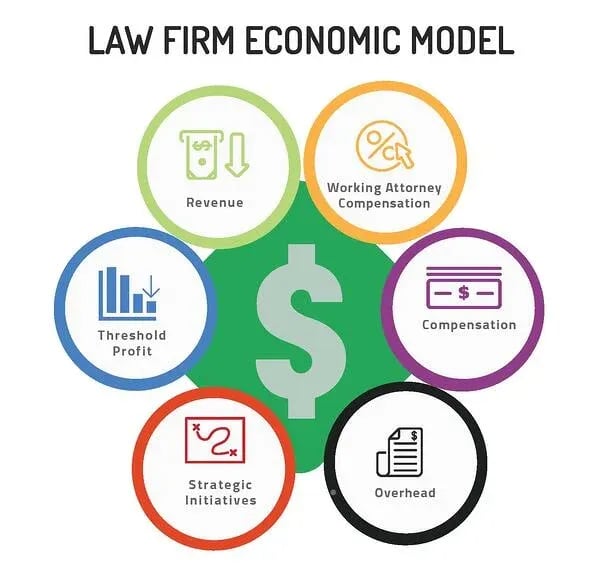

A law firm’s economic model defines how the firm runs from a financial perspective and allows a firm to:

- generate fees;

- pay lawyers for working attorney results;

- reward origination and other client management contributions;

- manage overhead;

- invest earnings for strategic purposes, and

- define the threshold (minimum) and targeted profit levels.

When a law firm can operate within a defined economic model, they have a competitive advantage. Viability erodes when a firm loses sight of its economic model, doesn’t have one, or fails to keep it current. In our experience, once a firm enters a decline phase, it has a less than 50% chance of regaining its edge.

The various parts of a law firm’s economic model are discussed below:

Revenue

The fees you collect, regardless of how you produce them (hourly, contingent, fixed, etc.), count as revenue. Profit models apply to all firms. The differences between firms are shown in their abilities to adjust to how revenue is earned; their pricing approaches, and their market fit.

For example, a firm that operates on thin margins and higher volumes (think insurance defense) will need a tighter variable (costs that increase with volume), cost model, due to the potential negative impacts associated with an increase in volume. In plain terms, if a firm is underperforming on each hour worked, more hours only make it worse.

Alternatively, the priorities of a firm with more profitable revenue streams may focus less on certain elements of their cost models and focus more on items that serve the generation of the higher-margin revenue (E.G. expanding the compensation range for talented lawyers). Cost management is also important to higher-margin firms but their models may have more slack in them or focus on different aspects.

We work with firms that make good money at both ends of the pricing spectrum, and we are not advocating one pricing approach over another. But we can say this for sure:

Firms who manage who they are rather than who they think they are

fare much better economically.

Understanding client price sensitivity within your markets, competitive supply, your firm’s capability, and capacity, and the level of market demand are all essential to creating your economic model.

It is important to first understand where your firm fits into the market and then build a model

to optimize performance in these parameters.

Working Attorney Compensation (non-owner lawyers)

We recommend a base and bonus approach to compensate lawyers for the work they produce with their own hands.

The most common approaches include lower base salaries and higher bonus pay and higher base salaries and lower bonus pay. Pros and cons come with each approach, but consistency is important. Frequent changes to compensation plans can cause instability in the cost structure, lawyer frustration, and turnover.

Compensation approaches are typically different for junior lawyers and senior lawyers. Generally, we recommend shifting compensation risk (increase in incentive compensation portion) to lawyers as they become more experienced.

Working attorney compensation typically ranges from 30% to 40% of fee collections. For highly profitable lawyers, additional bonus compensation is necessary to incent longevity and continued production.

Whether a working attorney receives a base salary, fee sharing formula or a combination, we recommend keeping the guaranteed portion within the 30% to 40% range and rewarding profitable timekeepers with a bonus after threshold profit is attained.

We will address setting a threshold profit level later but it is a necessary element of the bonus calculation.

A basic timekeeper profitability bonus formula is as follows:

Plus:

- Total fees collected (some firms use billed amounts if they don’t attribute collection risk to the lawyer)

Less:

- Guaranteed pay and benefits for working attorney results

- Direct overhead allocations (usually includes secretarial and other direct labor support)

- Allocated overhead (typically includes all costs less timekeeper and other direct overhead allocations) *

- Threshold profit (set by the firm - minimum profit expectation)**

*If a firm has a strong cost accounting system that can more precisely identify the variable cost items directly attributable to a timekeeper, a contribution margin approach (Revenue- All Related Variable Costs) is possible. In our example, we only allocate the more material direct cost items (payroll and benefits) and we use a general overhead allocation for the remaining cost after payroll allocations.

Finally, some firms apply an average employee benefits percentage in lieu of a specific percentage by an attorney. Their rationale is that they don’t want to build an economic model that relies on hiring lower benefit-cost employees.

**Including or excluding fee-sharing compensation for the origination portion of originated and worked timekeeper collections impacts the bonus percentage (a firm’s basic compensation theory is an important factor when creating an economic model ).

Result:

= Profit remaining for bonus participation

Bonus Calculation:

X % bonus percentage (Incentive set by the firm)

= Timekeeper profit bonus (profit remaining for bonus participation * the bonus percentage)

When setting the bonus percentage, it is necessary to remember that the amount left after paying bonus money to the timekeeper, must also compensate the originator of the work. An adequate threshold profit can protect the firm, but we suggest running a few assumptions before setting the bonus percentage.

Origination Compensation

Complex compensation systems, while often necessary to adequately weigh all pay factors, are often eschewed by lawyers. The result is that law firm compensation systems are frequently oversimplified and inadequate.

Regardless of the legal entity makeup (LLC, LLP, C Corp, Sub S) the recommended profit model only considers the total amount available (profit) to pay owners. How profit is split between the owners is not considered in the profit model. We mention it now because the partners’ compensation system can affect the pay of non-owner lawyers.

Origination pay at the non-owner level (a cost) is typically a portion of gross fee collections. Depending on the compensation plan, origination pay can vary and typically ranges from 10-25% of collections. In well-run firms, risk, profitability, and performance can all affect the pay rate for originations.

Again, equity partner compensation is a different subject and not considered in the economic model. The economic model is only concerned with creating the total pool of profit for the equity partners to divide.

Managerial Efficiency Compensation - Client and File Level

In most law firms, paying for working attorney and origination performance is well-established. Paying non-owner attorneys for file management responsibilities is more difficult and less common.

Junior lawyer supervision or operational client management is a justification we often hear when working attorney base compensation exceeds the typical pay range. For example, it is not unusual to encounter a senior lawyer whose pay exceeds 40% of their working attorney collections and who also has no origination credit to justify the compensation level.

When analyzing these situations, we sometimes find the compensation level reflects managerial efficiency at the client and/or file levels. To account for the managerial factor, we recommend an objective compensation approach to reward managerial efficiency. The funding for this compensation pool can come from the origination pool.

For example, assume a firm compensates 15% for originated work and desires to recognize client managerial efficiency. We recommend 3-5 % of relevant fee collections for client and file management contributions, which in this example would reduce the origination pool to 10-12%.

This approach is only applicable in situations where an originator has non-owner lawyers managing all or part of their caseload. Equity partners who share client responsibilities are typically rewarded under the equity lawyer compensation plan.

Setting the actual compensation percentage is best done after considering strategic objectives and the significance of the contributions.

Non-Attorney Timekeeper Billable Compensation

Compensation approaches to non-attorney billable timekeepers are typically less formulaic and essentially all base salary. Firms that have strong paralegal demand may have more involved systems. When building out your operating model, you can create a separate category for non-attorney billable timekeepers or you can include them in overhead. The choice depends on the value of the information and how it will impact decision-making.

Overhead

Overhead includes the remaining expenses that are not included in any of the compensation categories. How overhead is allocated within the firm affects its economic model if any aspect of timekeeper pay is profitability-based.

Often times overhead is considered a fixed cost or as an area with limited impact on the results of the firm. I am sure that you may have heard the expression about the limited value of counting paper clips. Again, this attitude toward overhead control is another oversimplification of an important element of a firm’s economic model.

All these areas are connected and if overhead is just a couple of points too high, it impacts the amount available for the people who deliver results, which can significantly impact the stability and profitability of a firm.

Typical overhead items include:

- All remaining payroll and benefits not considered somewhere else in the calculation

- Facilities Costs

- Practice Support Technology

- Practice Development

- General and Administrative

Fixed and Variable Overhead

It is possible to further organize these overhead costs into fixed and variable buckets. Fixed costs generally (to a point) don’t increase with more volume and variable costs increase incrementally with volume. Not to try to confuse anyone, but whether a cost is fixed or variable often depends on the measurement used. For example, if your software license costs are $100 per user and you add a new user your costs for the software increase by $100. If you are measuring cost per billable hour, the software license user cost does not increase with more hours. Again, the measurement is the key.

Good Overhead and Bad Overhead

Good overhead adds value to the client service experience or the efficiency of the firm. Bad overhead provides little or no value to the client service experience of the firm and decreases the efficiency of the firm. Excess office space, firm cars, apartments, unstaffed branch offices, and stadium suites are examples of overhead often hard to justify.

Good overhead is often lumped with bad overhead and can kill funding for innovation. For example, insufficient money for a marketing automation system because the rent is too high. Not only is the excess rent onerous, but it is crowding out funding for high-return investments.

A Question of Priorities

Nothing is more frustrating when we hear a managing partner or committee say they cannot afford an improvement to a mission-critical system or process. It is not a question of affordability, it is a question of priorities. In almost every instance, the elimination of bad overhead opens up funding for high-return investments.

The process of building an economic model forces the firm to confront their bad behaviors that lead to poor performance.

Creativity

Finding innovative ways to deliver client service without expanding overhead can make your firm competitively superior and a better choice for clients. For example, tracking important case handling KPI’s and quickly acting where indicated can improve client service. Here are a few statistics that can show areas that need attention:

- Average Days Files are Open

- Average Age of Open Files

- Average Age of Closed Files

- Caseloads by Attorney

Some overhead is unavoidable and even legally required, but overhead expenses should contribute to better client service wherever possible.

Strategic Initiatives

It is often difficult to allocate current year income to longer-term strategic initiatives. Defining opportunities that benefit all partners are challenging, but they exist. For example, consider the following investments:

- Hiring laterals who absorb excess capacity and reduce overhead per lawyer;

- Investing in future capacity (hiring lawyers in advance of need);

- Purchasing a marketing automation system that supports healthy client relationships and new business generation;

- Implementing case Management systems that support operational efficiency; and

- Utilizing advanced financial reporting that provides insights into client profit improvement.

There are many others. We suggest every firm allocate 2-4% of their current year's gross revenues to strategic initiatives. Firms that have a capitalization policy are better able to make strategic investments.

Threshold profit

When building an economic model, we recommend you consider a minimum acceptable profit level before paying incentive compensation. A threshold percentage of revenue or an absolute dollar value can work.

Setting threshold profitability forces a firm to consider the value they offer to the attorneys who work with the firm. For example, a firm may command a higher threshold profit if it can provide lawyers with better revenue-generating opportunities than are readily available in the marketplace. Put a steady stream of work together with a high billing rate, and the threshold can expand. Alternatively, firms that provide less value or lower rate structure may have to live with a lower threshold profit.

Accounting and financial modeling can only take you so far. Setting a threshold profit is a strategic exercise and a valuation of the firm's collective offering to attorneys. A tricky part is deciding whether the threshold profit level should apply uniformly across lawyers and practice areas within the firm. In our experience, some variation in threshold profit is necessary.

For example, higher billing rates or experienced lawyers can more easily meet the threshold profit targets than lawyers working on lower-rate clients. The threshold profit will vary if it is strategically preferable to hold different practice areas to different standards. Much also depends on how much control practice areas have over their overhead spending.

The easy part is to define the level of threshold profit. Much of this economic modeling is a result of manipulating the components. For example, suppose market wages for working attorneys average 35% of the amount a firm can charge clients for their services. In that case, the model must recognize this level of compensation, and management must look elsewhere for improvements.

Another difficulty arises when an economic model is at war with itself. Competing priorities can exist between practice areas that need a lower cost structure and those that are less focused on cost. In these instances, strong leadership and flexibility in the management approach to practice area cost management are necessary. For example, rigid hiring standards that apply uniformly to all practice areas can create serious issues. If the differences are too deep, it is difficult to maintain the construct of the firm - some stay and some leave.

Economic Model, Strategic Factors, and Tools

Building an economic model is as much a strategic exercise as it is a financial one. Both disciplines must have input into the process. No financial model ever implemented itself and plenty of strategic plans have failed due to insufficient profitability.

A good process, the right modeling tools, and experienced support can reduce the frustration, time, and fatigue related to creating a financially and strategically sound economic model.

.webp?width=124&height=108&name=PerformLaw_Logo_Experts3%20(1).webp)